The Whisky Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Excisemen

Attack of the Excisemen (1700s-1823)

The conflict intensifies across the Highlands...

The 18th century dawned on a Scotland where whisky had become more than a drink. It was identity, economy, and tradition distilled into liquid form. But the government in London, perpetually hungry for revenue and increasingly determined to control its rebellious northern territories, was about to transform whisky-making from a cherished tradition into an act of rebellion. What followed was perhaps the most romantic and defiant chapter in whisky's long history: the age of smuggling.

The Excise Tightens Its Grip

After the initial 1644 tax, successive governments continued to increase duties on spirits. By the early 1700s, the tax burden had become substantial enough to make legal distilling economically challenging for small Highland producers. The government established the Board of Excise, a dedicated body tasked with collecting duties and suppressing illegal distilling. These Excise officers, or "gaugers" as they were known, became the most hated men in the Highlands.

The Excise system operated on informants and enforcement. Officers had sweeping powers to search properties, seize equipment, and impose crippling fines. They could destroy stills on the spot, confiscate barrels, and arrest distillers. On paper, the system seemed robust. In practice, it faced an entire culture united in opposition.

Highland communities developed elaborate systems to warn of approaching Excisemen. Smoke signals from hilltops, the movement of washing on clotheslines, horn blasts echoing through glens—all served as early warning systems. By the time an officer reached a suspected site, the still would be cold, the evidence hidden, and the locals suddenly unable to speak English. The landscape itself conspired against enforcement.

Culloden's Shadow

The Battle of Culloden in 1746 fundamentally altered the relationship between the Highlands and the British government. The Jacobite defeat wasn't just a military loss but an existential threat to Highland culture. In the aftermath, the government implemented the Act of Proscription, banning Highland dress, bagpipes, and clan gatherings. Chiefs lost their hereditary jurisdictions. The traditional clan system, which had defined Highland society for centuries, was systematically dismantled.

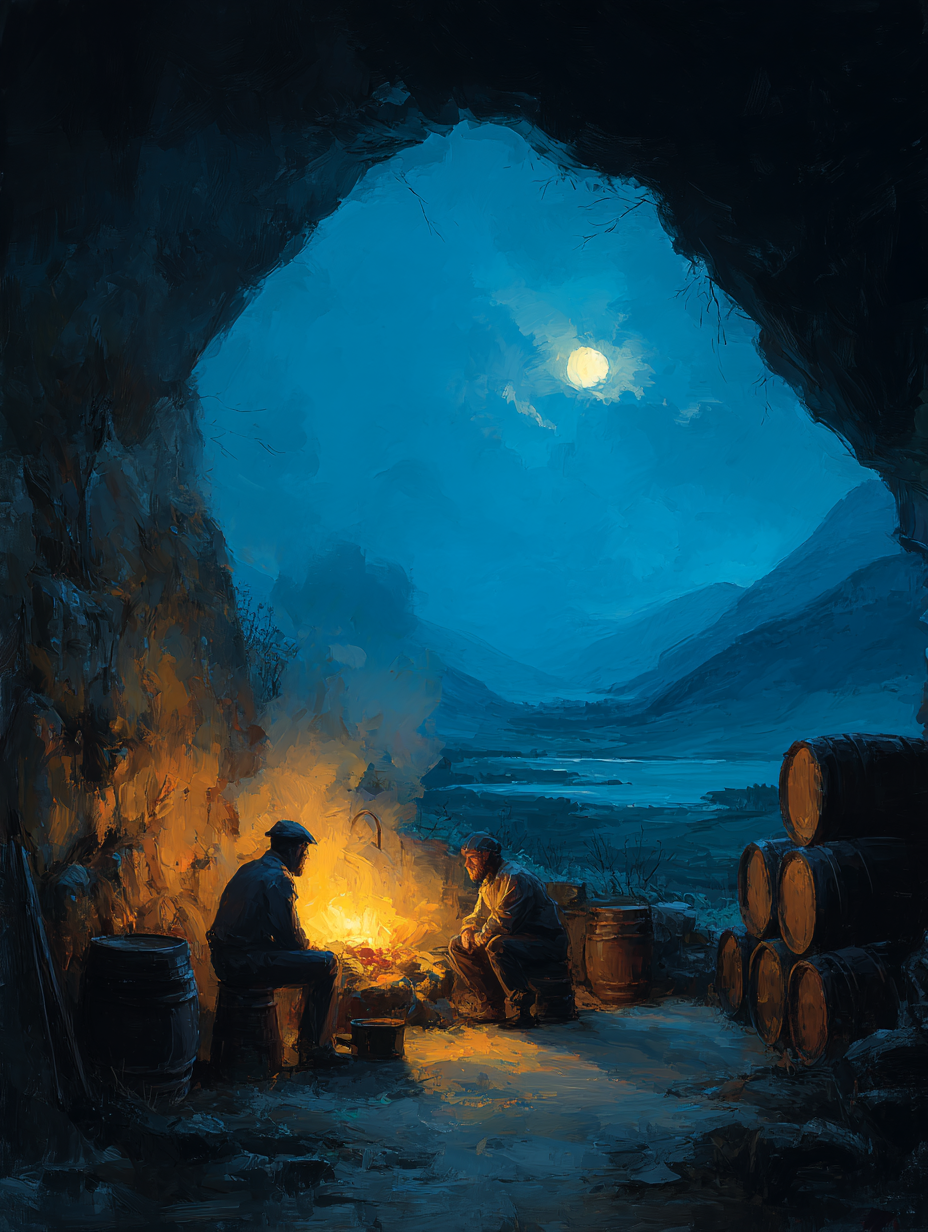

In this context, whisky took on profound symbolic significance. It was one of the few aspects of Highland culture that could continue, albeit illegally. Every hidden still became a small act of cultural preservation. Every successful smuggling run was a victory against the forces trying to erase Highland identity. The spirit that flowed through secret bothies wasn't just whisky—it was defiance made liquid.

The government's attempts to suppress illegal distilling intensified precisely because they understood this symbolic power. Controlling whisky meant controlling the Highlands. But the Highlanders had no intention of surrendering.

The Geography of Resistance

Did you know?

Some illegal stills were so well-hidden that their locations remained secret for generations. A few have only been discovered in recent decades, their stone foundations still intact in remote glens.

The Scottish landscape was perfectly suited to illicit distilling. The Highlands offered thousands of remote glens, hidden caves, and mountain valleys far from government oversight. Islands like Islay, Jura, and Skye provided natural fortresses, accessible only by boat and populated by tight-knit communities who could spot strangers immediately.

Illegal stills, or bothies, were masterpieces of concealment. Built into hillsides, hidden in caves, or camouflaged among rocks, they were designed to be invisible from a distance. Distillers used peat fires that produced less visible smoke than wood or coal. They worked at night, when darkness covered their activities. Some even diverted streams to create natural cooling systems that left no trace.

The size of these operations varied. Some were genuinely small-scale, a farmer making enough whisky for his family and perhaps some barter. Others were sophisticated businesses producing hundreds of gallons annually. The finest illegal Highland whisky commanded premium prices in Edinburgh and Glasgow, where customers knew that untaxed spirit was almost always superior to its legal counterpart.

Heroes and Legends

The smuggling era produced legendary figures whose exploits became folklore. Magnus Eunson of Orkney was perhaps the most famous. A church officer and lay preacher by day, he ran a massive smuggling operation by night. When Excisemen came searching, he famously hid barrels beneath a coffin in his home, draping white cloth over everything and having his family kneel in prayer. The superstitious officers, told that smallpox had claimed a victim, fled without searching.

Highland women played crucial roles in smuggling networks. They transported whisky in specially designed garments—tin containers strapped beneath their skirts allowed them to carry gallons whilst appearing merely stout. Officers were often reluctant to search women thoroughly, making them invaluable to smuggling operations.

The smugglers' knowledge of terrain was encyclopaedic. They knew every mountain pass, every ford across streams, every cave and hideaway. They could move at night through landscapes that would bewilder outsiders in broad daylight. Stories tell of smugglers leading Excisemen on wild chases through bogs and over cliffs, always staying just ahead, intimately familiar with ground their pursuers couldn't navigate.

The Quality Divide

A perverse situation developed: illegal whisky was consistently superior to legal spirits. Legal distillers, squeezed by high taxes, rushed production to maximise volume. They used whatever ingredients were cheapest, cut corners on fermentation, and sold their whisky as young as possible. The result was harsh, poorly made spirit.

Illegal distillers faced no such pressures. They could take their time, use the finest local barley, draw water from the purest springs, and follow traditional methods perfected over generations. They had reputations to maintain within their communities. An illicit distiller who produced poor whisky would find no customers and face social disgrace.

This quality gap created a flourishing black market. Edinburgh's fashionable drawing rooms and Glasgow's merchant houses preferred smuggled Highland whisky. Even as they publicly supported law enforcement, the wealthy privately paid premium prices for illegal spirits. The hypocrisy was blatant but persistent.

The Wash Act of 1784

Recognising that enforcement was failing, the government attempted a different approach. The Wash Act of 1784 created a geographical divide, establishing different tax rates for Highlands and Lowlands. The Highland Line became an official boundary, with lower taxes north of it intended to encourage legal distilling.

The Act backfired spectacularly. Rather than encouraging compliance, it created new smuggling opportunities. Highland distillers could produce cheaply under the lower tax regime, then smuggle their whisky south where it fetched higher prices. The traffic of illegal whisky actually increased. Additionally, the quality requirements for legal Highland whisky were so restrictive—limiting still sizes and production methods—that many distillers found compliance impossible.

The Act also inadvertently acknowledged what everyone knew: Highland whisky was different and superior. By creating separate regulations, the government effectively validated the distinctive character of Highland spirits, even as it tried to control their production.

Did you know?

The Highland Line created Scotland's first official whisky regions, inadvertently acknowledging that Highland whisky was fundamentally different. This geographic distinction (rightly or wrongly) still influences whisky classification today.

A Culture United

What made the smuggling era so successful wasn't just individual cunning but collective solidarity. Entire communities participated in or protected illicit distilling. A crofter might not distil himself but would never inform on his neighbour. Ministers preached against the sin of informing. Even local officials often turned a blind eye.

This solidarity wasn't merely about whisky. It reflected deeper resentments about land clearances, where landlords evicted tenants to make way for more profitable sheep farming. It embodied anger about cultural suppression following Culloden. It expressed economic desperation in communities where whisky represented one of the few sources of income. The spirit running through illegal stills carried the weight of all these grievances.

The few who did inform faced severe consequences. They were ostracised, sometimes violently attacked, their property destroyed. In Highland society, being known as an informer was perhaps the worst reputation possible. This social enforcement proved far more effective than any government penalty.

The Turning Point Approaches

By the early 1800s, the situation had reached a stalemate. The government was collecting far less revenue than intended, its enforcement efforts largely futile. Legal distillers, producing inferior spirits under crippling taxes, struggled to compete. Illegal distillers thrived but lived under constant threat. Excisemen risked their lives enforcing unpopular laws in hostile territory.

Something had to change. Voices within the government and the distilling industry began arguing for reform. The most compelling argument was simple: lower taxes might actually increase revenue by bringing illegal distillers into the legal fold. If legal whisky could match illegal quality, customers would have no reason to support the black market.

One man would prove crucial to this transformation. George Smith, an illegal distiller in the Glenlivet area, was about to make a decision that would reshape the entire industry. But his story, and the birth of legal Highland distilling as we know it, would have to wait for the next chapter.

The smuggling era was approaching its end. But the whisky it had protected, refined, and perfected was about to enter a new age.

Next time: Episode III - Revenge of the Scots, where bold decisions transform outlaws into businessmen and Highland whisky conquers the world.

If you missed it, go back and read: Episode I - The Phantom Spirits

Tasting Notes from the Era: To taste something reminiscent of smuggling-era whisky, seek out whiskies from distilleries that still use traditional methods and smaller stills. Edradour, Benromach, and independent bottlings from traditional distilleries offer glimpses into the robust, characterful spirits that made illegal Highland whisky so prized. Look for expressions with heavy peat influence and no chill filtration.