The Whisky Wars: Episode I - The Phantom Spirits

The Phantom Spirits (Pre-1700s)

A long time ago, in a glen far, far away…

Long before the great distilleries rose to dominate the Scottish landscape, before copper stills gleamed in purpose-built warehouses, and centuries before whisky became the amber nectar we revere today, there existed something more ancient and mysterious. The origins of Scottish whisky are shrouded in mist as thick as that which rolls across the Highlands at dawn — part history, part legend, and wholly magical.

The Ancient Keepers

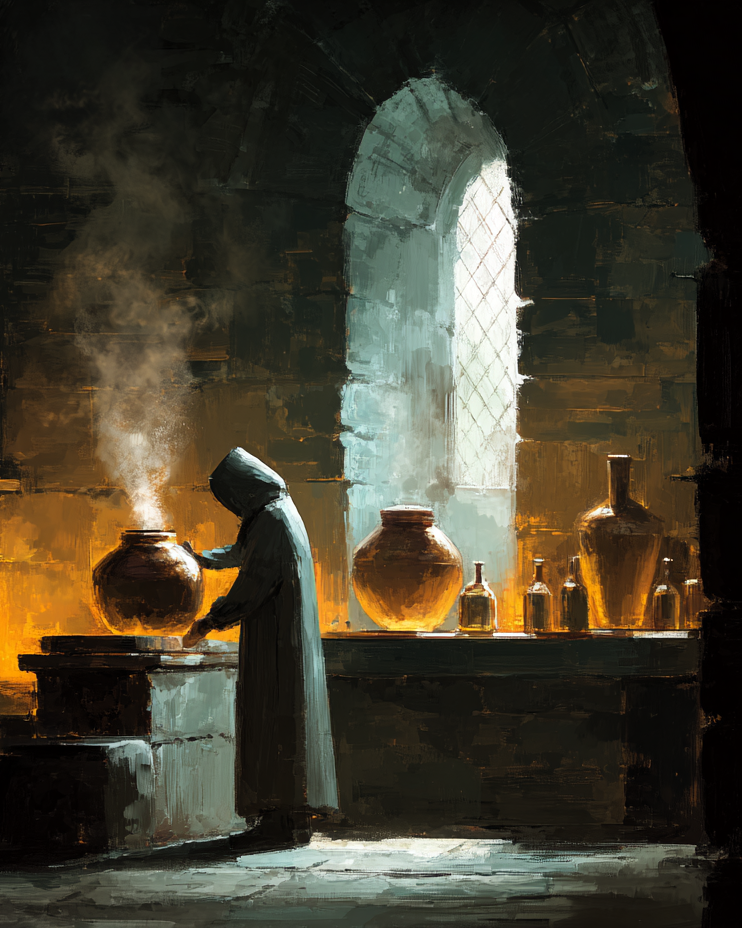

In the beginning, there were monks. Medieval religious communities were the original guardians of distillation knowledge in Scotland. They arrived from Ireland around the 11th and 12th centuries, bringing with them not just Christianity, but something perhaps more enduring: the knowledge of how to transform simple ingredients into uisge beatha — the water of life.

These monastic communities, scattered across Scotland in abbeys like Melrose and Arbroath, and on remote islands like Iona, understood distillation as both science and spirituality. They had learned the ancient art from European alchemists who had, in turn, inherited it from Arab scholars. But what those monks created in their stone buildings wasn't meant for pleasure or profit. Initially, this precious spirit was medicine, a curative elixir believed to prolong life, ease pain, and ward off disease.

The monks were the first Master Distillers, though they would never have called themselves that. In their cold stone rooms, heated by peat fires, they worked their alchemy with barley, water, and yeast. The equipment was primitive by today's standards — crude pot stills that would seem almost comically simple compared to the gleaming copper behemoths that would come centuries later. Yet they created something that would shape Scottish culture forever.

Did you know?

The word whisky comes from the Gaelic “uisge beatha”, meaning water of life. Over time, uisge evolved into usky and finally became whisky — the term we know today.

Knowledge Spreads Beyond the Cloisters

No secret remains confined to monastery walls indefinitely. By the 15th century, distillation knowledge had begun spreading throughout Scottish society. The first official record appears in 1494 — an entry in the Exchequer Rolls noting "eight bolls of malt to Friar John Cor wherewith to make aqua vitae". Eight bolls could produce around 1,500 bottles by modern standards. Clearly, Brother John wasn't just making medicine anymore.

As monasteries dissolved during the Reformation in the 16th century, monks scattered across Scotland, taking their precious knowledge with them. Suddenly, farmers and crofters throughout the Highlands and Lowlands began experimenting with distillation. What had been a monastic practice became a cottage industry, then a way of life.

Every farm with surplus barley and access to clean water became a potential distillery. In remote glens and on windswept islands, families developed their own techniques, their own secret methods passed down through generations. Each region's water, peat, and barley created unique characteristics — the terroir of whisky, though no one called it that yet. The spirit seemed to take on the character of the land itself.

The First Clouds Gather

But in 1644, everything began to change. The Scottish Parliament, desperate for revenue to fund military operations, imposed the first tax on whisky. It was modest at first, but it marked the beginning of a conflict that would define Scottish whisky for the next two centuries. The government had noticed the people's spirit, and they wanted their share.

The tax was more than an inconvenience; it was an existential threat to Highland culture. For crofters and farmers, whisky wasn't just a drink — it was currency, medicine, hospitality, and heritage. It marked births, sealed marriages, and commemorated deaths. The idea that the government could tax this sacred tradition felt like a violation of the natural order.

As the 17th century drew to a close, tensions between the government's hunger for revenue and the Highland people's determination to preserve their way of life continued to escalate. The conflict that would define the next century was already taking shape.

The Battle Lines Form

By the late 17th century, the foundations of conflict were being laid. The 1644 tax had been just the beginning. Subsequent increases in taxation and the appointment of Excise officers created a growing divide. On one side stood the government, seeking revenue and control. On the other stood the Scottish people, particularly the Highlanders, who viewed whisky-making as an inalienable right.

Already, a pattern was emerging. Those who paid the tax often produced inferior spirits, rushing production to maximize profit margins squeezed by government levies. Meanwhile, those who distilled illegally could take their time, use better ingredients, and follow traditional methods. Quality and legality were beginning to diverge.

The Excise officers of this early period faced an impossible task. Scattered across a vast, mountainous country with poor roads and hostile communities, they had limited power to enforce compliance. In remote glens and on distant islands, their authority meant little. The whisky-makers knew every hidden valley, every cave, every route through the mountains. The stage was set for a conflict that would intensify dramatically in the century to come.

The Spirit of the Land

Did you know?

Early distillers didn't choose peat for flavour—they used it because Scotland had few trees for firewood. The distinctive smoky character that defines many Scotch whiskies today was originally born of necessity, not design.

What made these early, illegal spirits so remarkable? The answer lies in the deep connection between whisky and Scotland's landscape. Highland distillers used local peat to dry their malted barley, infusing it with the smoke of their specific terrain. They drew water from springs and burns that had filtered through granite and heather for centuries. They stored their spirit in whatever casks they could acquire — sherry butts from Spain, wine barrels from France, even repurposed food containers.

Each glen developed its own character. The Speyside waters, flowing through gentle valleys rich with vegetation, created different spirits than the peaty, maritime waters of Islay where seaweed and salt influenced every drop. The soft Lowland whisky, made in more agricultural regions, differed markedly from the robust Highland style. Without formally understanding it, these early distillers were creating the foundation for what would eventually become the most diverse whisky landscape in the world.

The best distillers understood something profound: whisky wasn't just about following a recipe. It was about listening to the land, respecting the seasons, and understanding how each season affected the spirit. A harsh winter meant different barley. A wet spring changed the water character. Every batch was unique, tied to a specific moment in time and place.

Phantom Records

This period, roughly from 1500 to 1700, remains frustratingly difficult to document with precision. Most distilling happened informally, unrecorded and unregulated. We know it existed, we can trace its cultural impact through songs, poems, and court records of illicit distilling prosecutions, but specific details remain tantalisingly out of reach.

Who were the great distillers of this age? What did their whisky actually taste like? How did techniques vary from region to region before standardisation began? These secrets died with their makers, lost to time and the deliberate secrecy required to avoid taxation. The oral traditions that preserved distilling knowledge also meant that when a distiller died without passing on their methods, centuries of refinement could vanish overnight.

What we do know with certainty is that by 1700, whisky had become Scotland's spirit. It was woven into the fabric of Scottish identity so thoroughly that no government decree could unravel it. At Highland gatherings, whisky sealed agreements and celebrated victories. At funerals, it honoured the dead. At weddings, it blessed new unions. The spirit was inseparable from what it meant to be Scottish.

Did you know?

Most whisky knowledge was passed down orally, never written down. When a master distiller died without apprentices, centuries of refined technique could vanish overnight. Much of early Scottish whisky-making is lost to history.

The Storm Approaches

By the dawn of the 18th century, the stage was set for an epic confrontation. Whisky had evolved from monastic medicine to cultural cornerstone. The people had perfected techniques that created spirits of remarkable quality and diversity. But the government, always hungry for revenue and increasingly concerned with controlling the rebellious Highlands, was preparing to tighten its grip.

The taxes would increase. The Excise officers would multiply. The punishments would become more severe. But the Scottish distillers, particularly those in the remote Highlands and islands, had no intention of surrendering their heritage to bureaucrats in Edinburgh or London. They had something worth fighting for, and they knew every mountain pass, every hidden glen, every sea cave that could conceal a still.

The phantom era of whisky was ending. The age of smuggling — bold, dangerous, and legendary — was about to begin.

Next time: Episode II - Attack of the Excisemen, where we venture into the golden age of whisky smuggling and meet the rebel heroes who defied an empire.

Tasting Notes from the Era: While we can't taste 16th-century whisky, modern distilleries like Edradour (Scotland's smallest traditional distillery) still use methods that echo these ancient practices. For a glimpse of history, seek out traditionally-made Highland single malts that use local peat and traditional floor malting —distilleries like Springbank, Benromach or Kilchoman still practice these time-honoured techniques.